‘Casta Diva’ from Bellini’s ‘Norma’

Rosa Ponselle, soprano

Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra

Recorded Dec. 31, 1928 and Jan. 30, 1929

4:45

Rosa Ponselle was the first American-born, American-trained opera star. Born Posa Ponzillo in Connecticut in 1897, she began singing as a child to entertain silent-film moviegoers while the projectionist changed reels.

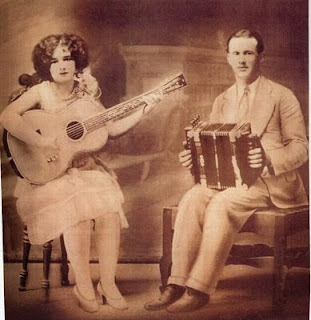

She became part of a double act with her older sister Carmela in 1915, working the vaudeville circuits. Meanwhile, she began formal voice training. Her teacher was so impressed that he convinced the great Italian tenor Enrico Caruso to listen to her. He was astounded by Rosa’s voice, and soon brought her to the stage of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where she appeared as Leonora in Verdi’s La forza del destino on Nov. 15, 1918.

Her success was immediate and long-lasting. Her most iconic role was that of the title character in Bellini’s Norma, about a druidic priestess and her unfaithful Roman lover. The Met revived its production for her after 36 years of neglect for the now-ubiquitous mainstay of opera seasons. The vocal selection is the emblematic “Casta Diva” aria from that opera.

Her incredibly powerful voice is apparent from the recording. Best known for her work in the lower registers, here she moves from high note to high note with effortless ease, spinning out notes with remarkable consistency.

She essayed 22 roles in 19 seasons at the Met. Ponselle’s stellar career lasted until 1937. Her success meant that native-born American singers would begin to receive a chance on the great opera stages of the world.

The National Recording Registry Project tracks one writer’s expedition through all the recordings in the National Recording Registry in chronological order. Next up: The Carter Family sings ‘Wildwood Flower’.