I don’t despise the French,

Allow me to apologize. I know it’s pretty standard to hate

them. They’ve always been good to me, though – very tolerant of my

gangster-film French and American enthusiasm.

I particularly love their classical music. Normally I don’t

ascribe to the virtue of one nation’s culture over another, but something about

their music is special. Maybe it’s the dynamic tension between the huge

cultural institutions and oversight France produces, and the counterbalancing impulse

not only to rebel against conventions, but to disregard them entirely. Keeps

things fresh.

Sometimes this combination of gutsiness and playfulness can

backfire, leading to thin, arch work that doesn’t resonate. Still, the batting average

is pretty damn good, and the dozen listed here are consistently rewarding to

hear.

Here’s a subjective list of my 12 favorites. Please note

that there are many that almost made it, and are certainly worth listening to –

Halevy, de Machaut, Delerue, Auric, des Prez, and more. I am counting out

Chopin and Stravinsky – each has typed himself unmistakably as a son of his

country of origin. AND there are many French composers that drive me NUTS –

Gounod, Massenet, Rameau, Lalo, Lully, Ravel, Boulez . . .

So here we go.

Marin Marais (1656-1728)

Master of the viola de gamba, he was not afraid of

complexity and dissonance, and created conceptual pieces such as “Le

Labyrinthe,” “La Gamme,” and the “Tableau de l’Operation de la Taille.” A busy

guy, he had 19 children. His life was horribly misrepresented in the film “Tout

les Matins du Monde.”

QUALIFYING ANECDOTE: He hid under his mentor Sainte-Colombe’s

special practice treehouse in order to steal his bowing moves. The little

sneak.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Sonnerie de St-Genevieve du Mont-de-Paris

Suite from “Alcyone”

Le Labyrinthe

Francois Couperin (1668-1733)

Called Couperin le Grand to distinguish him from his musical

relatives. It’s unknown whether this bothered them tremendously. An adventurous

keyboardist who fused French and Italian styles and who vastly extended the

expressive quality of the harpsichord. His work inspired Bach, Brahms, Richard

Strauss, and Ravel.

QUALIFYING ANECDOTE: To sell some of his early sonatas, he

packaged them under a fake Italian name – Italian composition was all the rage

and a French composer of the time couldn’t get arrested. They were wildly

successful.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Pieces de clavecin

Two Mass settings for organ

Motets

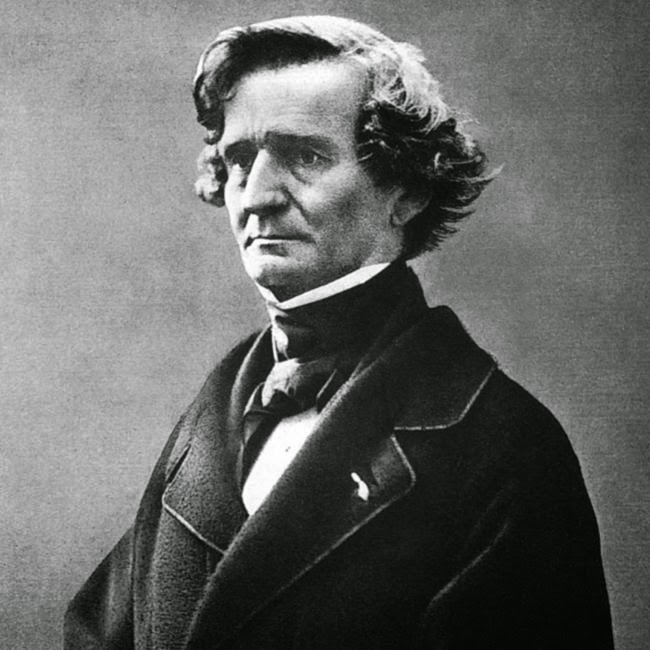

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869)

For some reason, most classical music lovers refer to the

“three B’s” – Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. What about Berlioz? He was the first

French Romantic. He invented modern orchestration (his ideal orchestra was 467

strong and included 30 pianos, 30 harps, and 12 cymbals); he was a masterful

conductor; incredibly literate, a devotee of Virgil, Goethe, and Shakespeare, his

criticism and memoirs are still instructive and enjoyable.

But somehow he squeezed “Symphonie Fantastique,” “Harold en

Italie,” the song cycle “Les nuits d’ete,” “Messe solennelle,” “L’enfance du

Christ,” “La damnation de Faust,” and the magnificent grand opera “Les Troyens”

– the last so grand that it wasn’t performed uncut until 147 after its

composition.

QUALIFYING ANECDOTE: Always falling in love, he basically

stalked his first wife, actress Harriet Smithson, for years until she gave in.

It didn’t work out. He planned to murder a fiancée that rejected him. Five

years before he died, he wrote: “My contempt for

the folly and baseness of mankind, my hatred of its atrocious cruelty, have

never been so intense. And I say hourly to Death: ‘When you will.’ Why does he

delay?” Not a happy guy.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Les Troyens

Symphonie Fantastique

Requiem

Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880)

The funniest of all classical composers, Offenbach could

mock anything and get away with it. He composed more than 100 comic works; his

final work, “Les contes d’Hoffman,” was decidedly serious but still delightful.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Orphee aux enfers

Le belle Helene

Les contes d’Hoffman

Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

“Carmen.” That’s all you need to know. The birth of real

passion and verismo in opera with an unforgettable and complex central figure.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Carmen

Jeux d’enfants

Symphony in C

Gabriel Faure (1845-1924)

Although he is better-known for his somewhat fluffy

“Requiem” and “Pelleas et Melisande,” his piano pieces are fascinating, as are

his songs, and chamber pieces. His work is clear, unified, as graceful as

falling water. He was a marvel at the organ, but despised it, and left behind

no compositions for it.

QUALIFYING ANECDOTE: He lost a job at a regional church as

its organist when he showed up to play for Sunday mass still in his evening

clothes from the night before, having never gone to bed.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Chanson d’Eve

Piano Trio

Works for solo piano

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

“For better or worse Claude Debussy must be seen as perhaps

the most influential figure in twentieth-century music.” – David Mason Greene.

His ears, perched on his bumpy oversized head could hear what others could not,

and got it down on paper.

QUALIFYING ANECDOTES: He was, according to Mary Garden, who

originated the role of Melisande in “Pelias et Melisande,” a “very, very

strange person.” His funeral procession moved through the abandoned streets of

Paris during a German bombardment of World War I. He was played, oddly enough,

by Oliver Reed in Ken Russell’s fanciful documentary “The Debussy Film.” His

wife had previously been Faure’s mistress.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Images for orchestra

Etudes for piano

La Mer

Erik Satie (1866-1925)

A free spirit, he is still ahead of his time. His work,

embossed with absurd titles such as “Cold Dreaming,” “Four Flabby Preludes,”

and “Desiccated Embryos” was alternately brilliant deconstructions of staid

musical forms, and new, unbound work that didn’t obey harmony, rhythmic

pattern, or any other musical norm. Ravishingly beautiful.

QUALIFYING ANECDOTES: He purchased 12 identical gray

corduroy suits, and simply rotated through them day after day. He made sketches

of imaginary buildings and kept them in a filing cabinet. Some of his best

compositions were found and published after his death – they had fallen behind

the back of his piano and Darius Milhaud found them there after Satie’s death.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Works for piano

Socrate

Parade

Joseph Canteloube (1879-1957)

Like many of the nationalist composers of his time – Bartok,

Janacek, Kodaly, Dvorak, and Smetana – Canteloube was a much a musicologist as

a composer, traveling and researching regional, vernacular music with vigor.

His “Songs from the Auvergne” took nearly 30 years to compile and complete.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Chants d’Auvergne

Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979)

One of the most knowledgeable, conductors, and teachers in

history, Boulanger was an incredibly gifted interpreter of music. She trained,

among others, Copland, Glass, Gardiner, Quincy Jones, Carter, Barenboim, and

Piazzola. In her own right, her delicate songs and chamber pieces are wonderful

– and unjustly overlooked.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Songs

3 Pieces for Cello and Piano

Fantasy for piano and orchestra

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

Absolutely true to himself, Poulenc could write both the

most absurd and transgressive works (“Les mamelles de Tiresias,” in English

“The Tits of Tiresias,” after Apollinaire, whom Poulenc met shortly before the

latter’s war-wound-related death) and the most movingly spiritual (“The

Dialogues of the Carmelites,” “Litanies a la vierge noire”). “I wanted music to

be clear, healthy, and robust,” he wrote.

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

The Dialogues of the Carmelites

Les mamelles de Tiresias

Songs

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992)

Still far ahead of us. His slippery, spiky, otherworldly

journeys can drive you mad, but if you sit down and push through them, the

listening will reward you. He could and did absorb Western and non-Western

styles; like a sculptor, he subordinated the elements he needed and used them

to create a singular voice. He was a masterful organist. His study of birds led

to many of his most striking compositions, such as “Oiseaux Exotiques” and

“Catalogue d’oiseaux.” He was imbued with a profound sense of God, and this

intense spirituality permeated his meditations, such as his “Concert for the

End of Time,” his nature studies such as “From the Canyon to the Stars,” and

opera and oratorio such as his epic “Saint Francoise d’Assise.” He said, “I

want to write music that is an act of faith, a music that is about everything without

ceasing to be about God.”

SUGGESTED LISTENING:

Catalogue d’oiseaux

Des Canyons aux etoiles . . .

Saint-Francois d’Assise

.jpg)